NOC

NOCBattling rough waves and strong winds, three engineers brought a yellow submarine ashore in Scotland this week.

With sheets of water pouring from its body, the UK’s most famous robot – Boaty McBoatface – was captured after 55 days at sea.

“It’s a bit slippery and the ocean winds have come in. There’s some stuff growing on it,” says Rob Templeton, now dismantling the 3.6m robot in Leverburgh, on the Isle of Harris.

Boaty has completed a scientific odyssey of more than 2,000 km from Iceland that could change what we know about the pace of climate change.

It was hunting for marine snow – “poo, basically” in the words of one researcher. This refers to small particles that sink to the bottom of the ocean, storing large amounts of carbon.

The deep ocean, referred to as the “twilight zone”, is extremely mysterious. Acting as the scientists’ eyes and ears, Boaty went there on the longest voyage yet for his class of submarine. BBC News had exclusive access to the expedition.

Gwyndaff Hughes/BBC

Gwyndaff Hughes/BBCThe public first chose the name Boaty McBoatface for a polar ship in 2016. That didn’t happen, but instead the name was quietly given to a fleet of six identical robots at the National Oceanographic Center in Southampton.

This last epic journey from Iceland was a great test of engineering. “Boaty has absolutely passed. It’s a massive relief,” says Rob.

It’s been a round-the-clock operation, with engineers sending text messages to the robot via satellite. “We tell it to dive here, travel there, turn on that sensor,” he says.

NOC

NOCIt’s exciting technology, but the science Boaty was doing could be part of a game changer in how scientists understand climate change.

They want to understand something called the biological carbon pump—a constant, massive movement of carbon within the oceans.

Small plants that absorb carbon grow near the surface of the ocean. Animals, often microscopic, eat the plants and then make branches. Those particles—marine snow—sink to the bottom of the ocean. This keeps the carbon locked up and reduces the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, one of the drivers of human-caused climate change.

But that carbon pump is still largely a mystery to scientists. And they are deeply concerned that the warming of our oceans caused by climate change is disrupting that cycle.

Packed with sensors and instruments in his belly, Boaty was transformed into a mobile laboratory to help scientists.

Cruising at 1.1 meters per second and submerging thousands of meters, Boaty had more than 20 sensors that monitored biological and chemical conditions such as nutrients, oxygen levels, photosynthesis and temperature.

It’s all about a major research project called BioCarbon, run by the National Oceanography Centre, the University of Southampton and Heriot-Watt in Edinburgh.

I spoke to two of the scientists, Dr Stephanie Henson and Dr Mark Moore, when they were at sea in Iceland in June on the project’s first cruise.

The skies were clear and the water was sparkling, making perfect conditions for dropping instruments hundreds of meters down and retrieving traps filled with sediment or microscopic marine life.

Gwyndaff Hughes/BBC

Gwyndaff Hughes/BBC“We’re measuring what’s happening in the upper ocean with the phytoplankton, the plants that grow there. We’re looking at the tiny zooplankton, the animals that eat them. And we measured the fecal pellets, the excrement that the animals produce,” explained Stephanie.

“Our climate would be significantly warmer if the carbon pump wasn’t there,” Stephanie said.

Without it, carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere would be about 50% higher, she says.

But current climate modeling doesn’t do the carbon pump justice, she says.

“We want to know how strong it is, what changes its strength. Does it change from season to season and year to year?” she says.

NOC

NOCThe waters off Iceland attract large amounts of plant and marine life in the spring, making it ideal for scientists to test how life interacts with carbon dioxide, Mark explains.

There are preliminary signs from the research that the carbon pump may be slowing down, the scientists explain. The team recorded much smaller “blooms” of plants and the small animals that feed on them than expected in the spring.

“If this trend were to continue in the coming years it would mean that the biological (carbon) pump could be weakened, which could result in more carbon dioxide being left in the atmosphere,” Stephanie said.

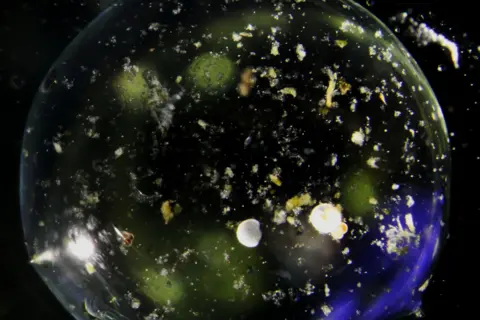

In the coming months, they will process their results – they have already shared some initial images of the extremely small life seen under the microscope.

NOC

NOCThey hope their work will feed into larger climate models that predict how and when global temperatures will rise and which countries will be most affected.

Dr Adrian Martin, who leads the BioCarbon project, explains that the research aims to better understand how the oceans store carbon through a controversial area of study called geoengineering.

Some scientists and entrepreneurs believe that we can artificially alter the ocean, for example by changing its chemical composition, in the hope that it will absorb more carbon. But these are still very experimental and have many critics. Opponents worry that geoengineering will cause unexpected damage or not address climate change quickly enough.

“If you’re going to make interventions that could be global concerns of the ocean ecosystem, you have to understand the consequences. Without that, you’re not informed enough to make that decision,” he says.

NOC

NOCWith the first phase of research completed, Boaty is on his way home to Southampton.

In a few weeks the scientists will return to Iceland – to compare life there in spring with autumn.

Their findings could mean we better understand how our warming planet will change and find solutions to limit the damage.

Additional reporting by Gwyndaf Hughes and Tony Jolliffe